Joey: 25 years on

25 years after his tragic death, Mark Graham and a host of greats remember the racer who will forever be intertwined with the TT: the incomparable Joey Dunlop

By Mark Graham Photography Bauer

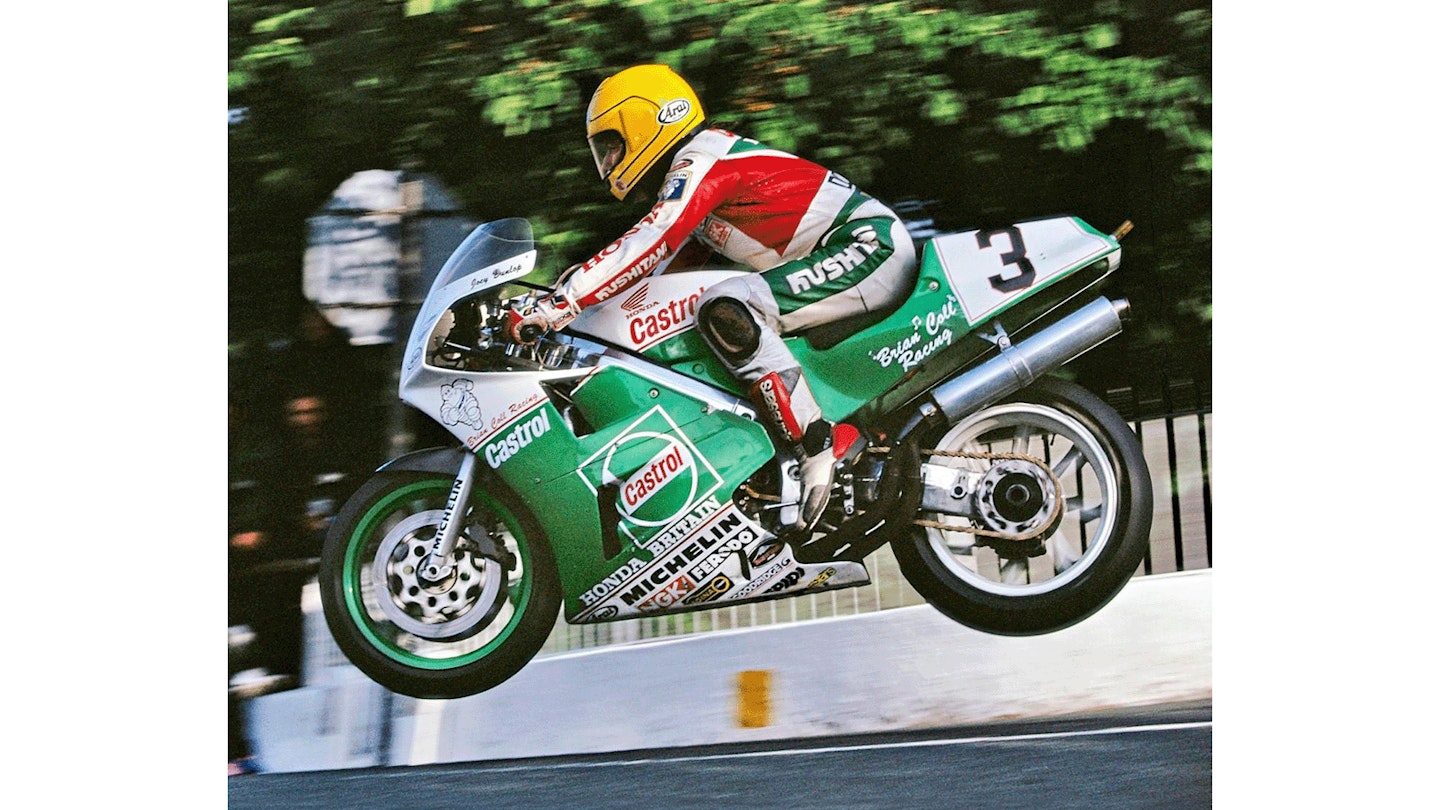

Joey, an RC30, sunshine, and the Isle of Man. Glorious

No good wondering how a man who amassed 26 Isle of Man TT wins could perish on the 4.2 miles of the Pirita-Kose-Kloostrimetsa Circuit in Estonia. Racing is dangerous. Racing on roads riskier yet.

Doesn’t matter where an immovable obstacle is. A tree is a tree wherever it might be. Stone walls are stone walls regardless of location. Every rider knows that. Respects the fact.

Yet somehow Joey’s demise seemed the oddest, cruellest event. A man who made pure road racing seem the most natural pursuit met his end when the negative realities of piloting anything from a 125 to a 1300cc proddie bike at speed bit awfully hard.

It happened he was on a 125. A class he began riding after the serious 1989 Brands Hatch crash that might have finished his career. His recovery took months, his attitude to racing did not waver: ‘I was told it wasn’t my fault, so that’s okay,’ he said.

Joey’s death on 2 July 2000 was the starkest reminder that even the finest practitioners of a dangerous game are not immune from the worst consequences. It never seemed possible with Joey until it happened.

There seemed something other-worldly about Joey. Like all the best sportspeople he made his craft look easy, unhurried, almost gentle. If the best footballers seem always to have more time and space, the best darts players an effortless action, Joey looked relaxed and fluid on a bike.

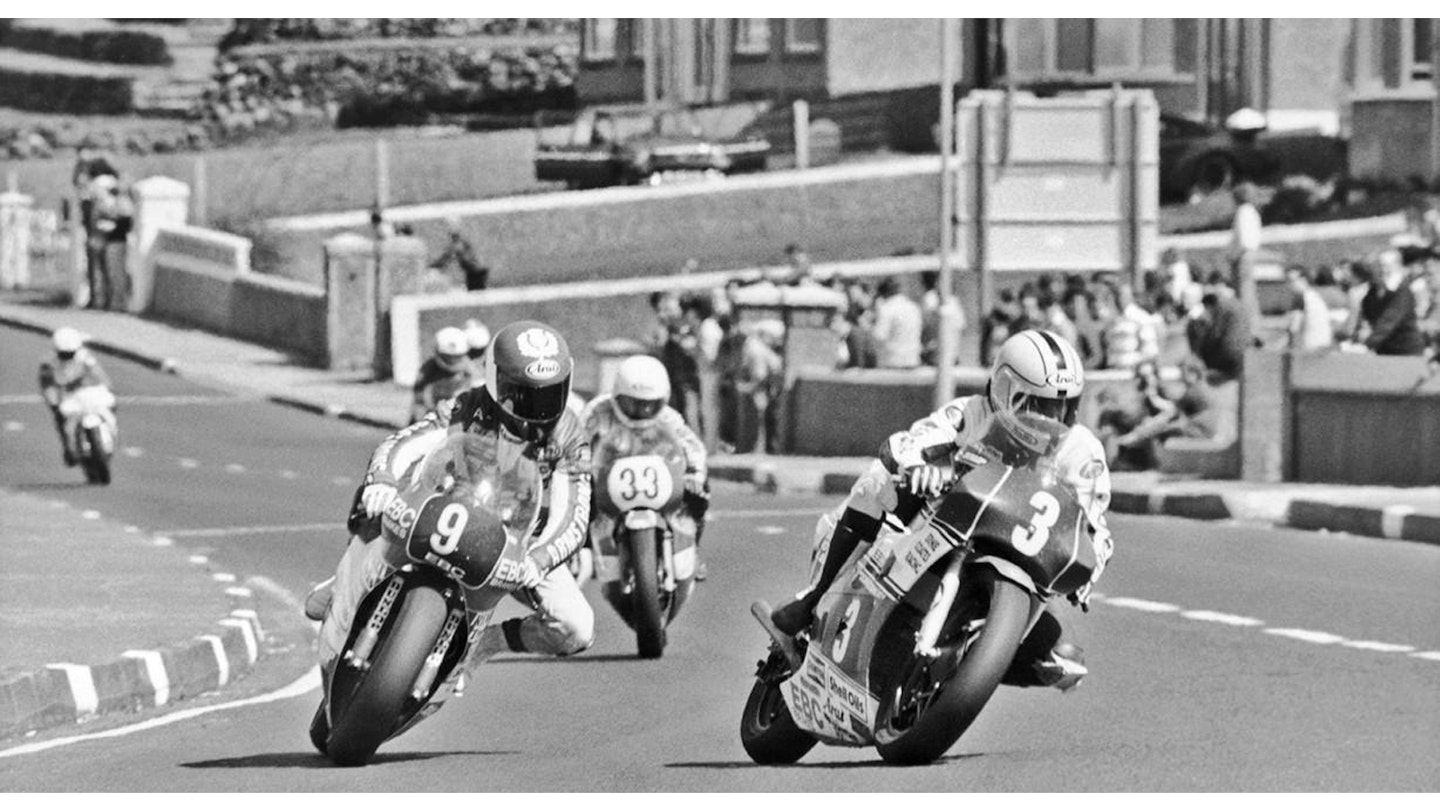

With Philip McCallen, 1991. Trying to remember what time the party finished last night

‘He was smooth,’ says 11-times TT winner and a Honda teammate of Joey’s, Phillip McCallen. ‘He knew exactly where to be and when, and in all conditions, too.’ McCallen’s all-action style was absolute inverse of Joey’s economic progress. A pell-mell full gallop to what seemed like Joey’s measured, brisk canter.

‘Joey was smart about picking his races too,’ says McCallen. ‘He’d maybe do five or six races at the Ulster, but he knew which ones he could win and he’d go all out in them. It might even be one race he’d target. And he’d pick his races with DJ [the late Dave Jefferies], too. Although DJ couldn’t beat him when he was on form.’

DJ’s uncle Nick Jefferies, himself a TT winner, said: ‘Joey was a great tactician. When he wasn’t the fastest, he knew he was consistent and could win races through guile. He was a bit like the great Stanley Woods in that.’ Irishman Woods won 10 TTs in the 1920s and 1930s.

Joey wasn’t a bluffer, but his relaxed paddock attitude and contrasting track behaviour could startle people. ‘At our local tracks when I was just starting out, he’d turn up to run-in his new Hondas,’ says Grand Prix winner Jeremy McWilliams. ‘You’d think he wasn’t interested, his lap times weren’t that fast… then in the main 250 race he’d just smoke everyone.’

Classic TT, 1981. Black paint was Honda protest at that year’s Formula One result

Joey’s reasons for riding number three at the TT were typically cogent: ‘The first bike always gets the birds,’ he said. ‘If I go at number three I miss that, the marshals are all alert, and if I can get past the first two riders I’ve got nobody in front. I like an open road so I can go as quick as I can without having to pass people.’

Joey’s race craft was key, as was his meticulous machine prep. ‘He hardly ever retired from a race,’ said Jefferies. ‘I first ran into him in 1975 at the Skerries 100 when he was still Joe Dunlop. This scruffy local Irish lad who could ride amazinglyquickly. He was fast and he always got his bikes going well. It didn’t matter what they looked like – him or the bike – but they were fast and reliable.’

And he set them up exactly as he wished, even when he was a factory Honda rider: ‘You’re setting them up so they’re easy to ride, almost soft, so they handle well at the TT.’ No one could argue with the results.

‘He talked to you with his eyes, if you were smart enough to pick it up. You could see what he thought by his face, his body language’

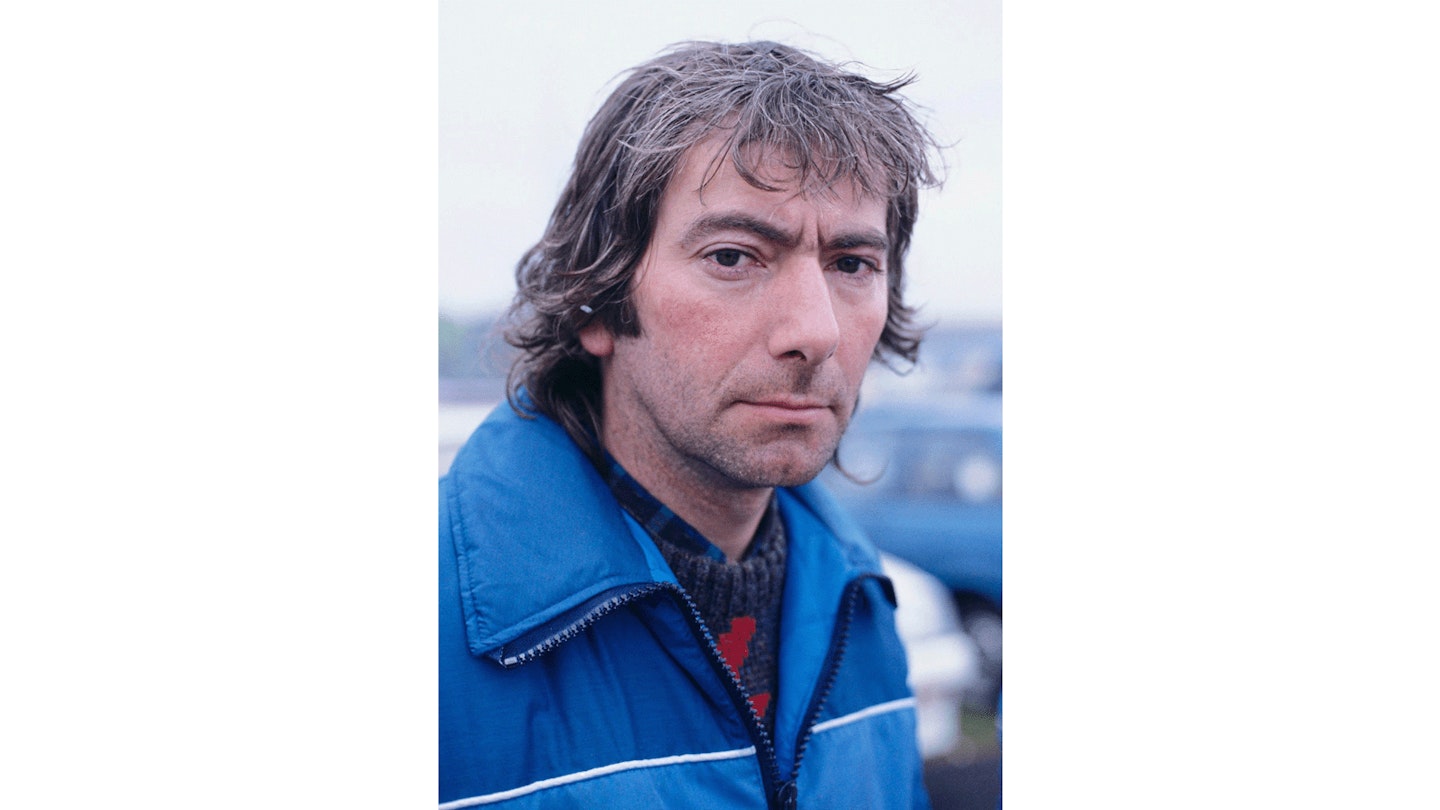

Mischievous glint suggests he inked the camera’s viewfinder before this was taken

As Joey’s mechanic the late Jackie Graham said: ‘He’d been rebuilding engines since he was 10. He was extremely dedicated – in his own way.’ And his own way was precisely what made Joey so appealing as a top rider. When the competition were currying media favour, Joey was busy saying very little.

Not that he didn’t have the ear of the press. During TT fortnight he could regularly be found in The Saddle, in Queen Street, just behind the North Quay of Douglas Harbour deep in conversation with the late Norrie Whyte of MCN. There was more ale drunk than shorthand notes taken, but the connection was there.

Other riders would struggle to understand the very singular Joey. He was not a gregarious character. His circle of friends was small and very tight, and he kept it that way. ‘All those wild parties,’ said Jefferies. ‘They were closed shop affairs. Once he trusted me we got on, but he was quite a guarded man.’

McWilliams remembers a man who liked a pint; a social drinker. ‘We were standing in the Mondello café at lunchtime on race day,’ he said. ‘And Joey was having a pint. We still had a couple of races to go.’

‘He adored what he did, and he did it his way, even when paired with the mighty Honda organisation’

Defying gravity over Ballaugh Bridge, 1992

His relationship with McCallen was slow burn. ‘When I started to do well in 1984/5,’ said McCallen, ‘I knew him to say hello to and the first time I beat him in 1988 I think he respected me from then. I had a new 250 that year then broke my foot at the North West 200, so I lent him some bits for his 250.

‘I was supposed to join Honda for 1989, but they had too many riders so I went to Kawasaki, but it wasn’t really working out. I called into his bar and we were sitting there talking – he’d had his Brands crash and he said, “Phillip, you should have my bikes. I’ll ring Honda in the morning”. He did – and then I was a Honda rider. He was a man of truth.’

If he had spare parts he’d lend them out in the paddock, and even take bits off his own bike to loan if required. But Joey’s greatest deeds were performed at a steady 60mph in his Merc van en route to the war-torn Balkans in eastern Europe to distribute clothes and other necessities.

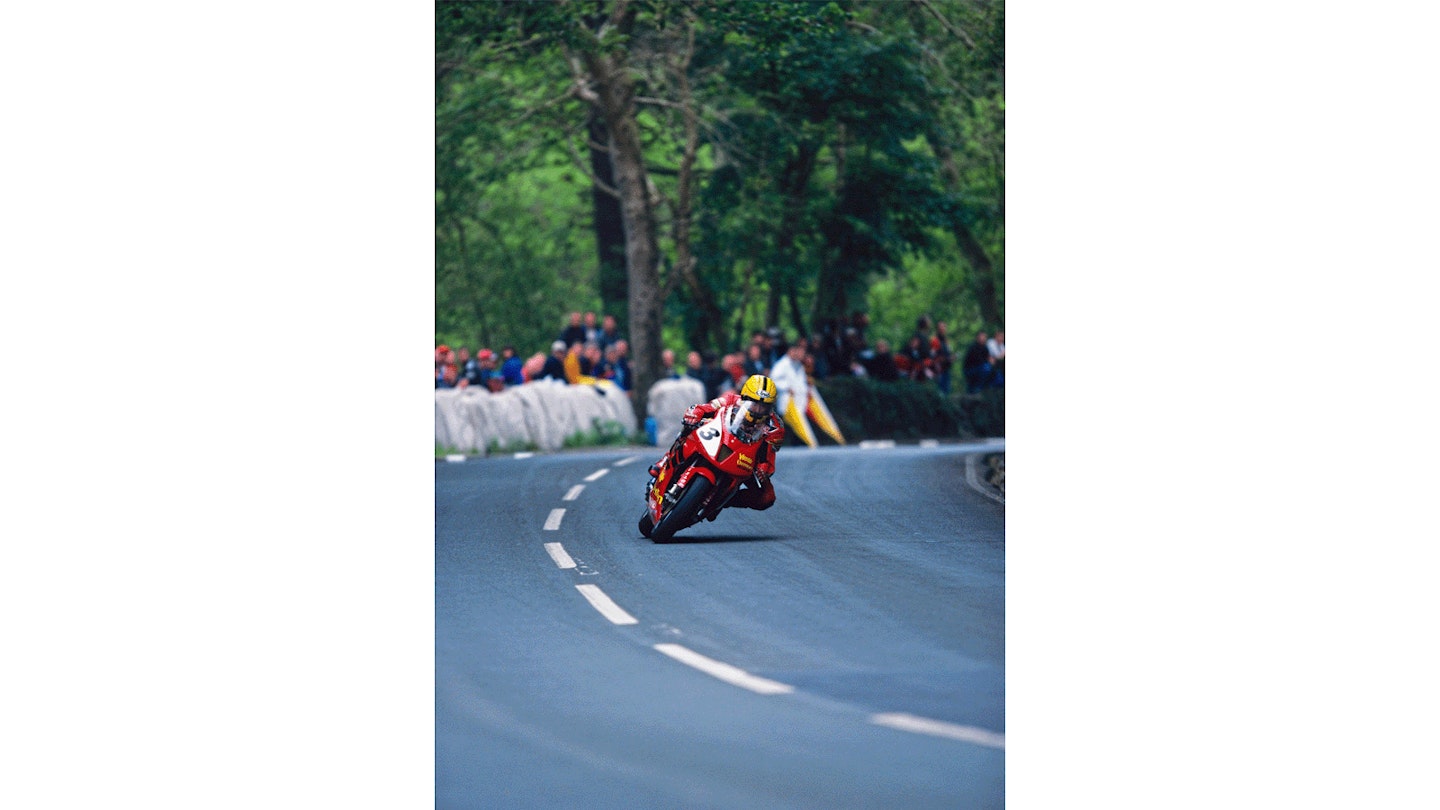

Honda SP-1, 2000 Formula One TT. Joey’s greatest win, celebrated overleaf

These were long hauls. He’d sleep in the back of the van, on a bench propped across the floor by the rear doors. He’d eat tinned soup, blithely traverse war zones and cross hostile borders to deliver his precious cargo.

He did it time and again to no fanfare, for no reward save that of improving the lives of innocent victims of dumb wars. He would no doubt have preferred his actions to have gone unnoticed, but he was made an OBE for his efforts in 1996 to go with his 1986 MBE for mere success on a motorcycle.

He never said much because, unlike many people, he never thought he had to. Almost monosyllabic in unfamiliar company, he was only slightly more voluble with those he knew. ‘He hardly talked at all,’ recalled Ron Haslam. ‘You could watch telly and have a cup of tea with him and if you got a couple of words you’d be doing well.’

McCallen again: ‘He talked to you with his eyes, if you were smart enough to pick it up. You could see what he thought by his face, his body language. And he was mischievous when he was relaxed. He literally stole my wife at my wedding when there was a white Gold Wing there for me and the bride. Next thing you knew he was away up the road on it with her on the back.’

Guthrie’s, RC45, 1997. Birds long gone

He was the consummate roads rider. ‘He was fast on the fast bits,’ said Nick Jefferies. ‘He was careful on the brakes, very safe on braking, and always slow into turns and fast out, so quick on the big corners.’ No one makes up time on slow corners, it’s the fast turns that separate the aces from the also-rans. Joey knew that from day one on a 200cc Triumph Tiger Cub.

Joey attracted fans to roads racing because he made a dangerous sport look like an art form, because he was as down to earth as the fella next to you in the crowd, because he was his own man and cared not a hoot for pomp or hoopla.

He adored what he did, and he did it his way, even when paired with the mighty Honda organisation.

The great Spanish bullfighter Luis Miguel Dominguin said: ‘Death is only a risk. The risk is the very essence of life itself.’ All the finest hard sports stars know that – from boxers, to mountaineers, to motorcycle racers. Joey knew it.

RS125, 1993. Lid/bike colour combo never been bettered

Joey by numbers

» His tally of significant roads wins is testament to his domination of the 1980s and 1990s. Only his nephew Michael Dunlop has now amassed more TT victories. Joey won 24 Ulster Grands Prix on anything from 125 tiddlers to 1000cc Superbikes and everything in between. He won 13 North West 200s, five TT F1 World Championships, and we haven’t even touched on the countless Tandragee, Cookstown, Skerries, or Killalane triumphs. Behind the relaxed demeanour was an efficient and almost merciless winning machine.

Joey leads Niall Mackenzie (9) at the NW200

Priority for protection www.araihelmet.eu